"With the rise in mental illness there is an increasingly strong need for therapeutic spaces," writes architect Abigail Freed. "Therapeutic architecture," she argues "lessens the need for the typical patient-doctor relationship. The space itself becomes the 'therapeutic apparatus'."

What a fascinating idea!

I've been told by some clients that our initial design interview is "a little like psycho-analysis." Architect Richard Neutra, a friend of Sigmund Freud, made that connection explicit. Explains Freed:

He required his clients to keep diaries and subjected them to a lengthy interview process. These tactics were Neutra’s way of gaining insight into their daily lives, their conscious and unconscious desire, their habits, their personal and interpersonal struggles and triumphs, as well as their deepest thoughts and feelings. Neutra believed that “architecture should operate like psychotherapy by assisting clients to satisfy unconscious psychical desires” and that the architect “operates on the basis of an emotional dynamic with a client developed through analysis of childhood experience.” From this process he felt fully equipped to create a physiologically curative design.”

Bethany Morse outlines his four-fold "biorealist" approach:

Abigail Freed outlines some of the "design tactics" Neutra used to fulfil the brief he gave himself, to better connect the "subject" to their environment and "imprint" upon them better mental habits.

One of the most notable features “of Neutra’s work during the 1950’s was an intense concentration on dismantling conventional barriers between inside and out.” He achieved this effect through the implementation of various tactics such as transparent glass, “spider legs” and mitred glass corners.

In all of Neutra’s post war houses there is an emphasis on the glass exterior.

In the Rourke house (1949) “the outside world intrudes through large glass panels. These are not simply picture windows that frame views or glass walls that structure the house as in traditional… instead the glass window/wall is actually a door that moves and permits movement. The wide overhang of the roof creates a zone of shadow attenuating and extending the boundary of the interior. The overhangs that all but eliminate reflection further reinforce the indeterminate simultaneity of enclosure and exposure. The glass becomes not transparent but invisible to leave the house unbounded.”

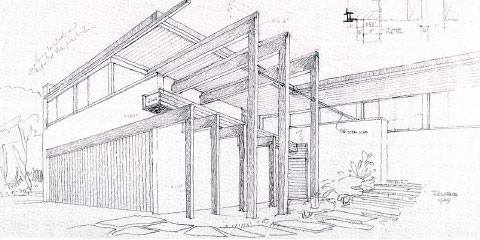

Neutra used his Spider Legs (pictured above) “to collapse the normally primary architectural distinction between exteriority and interiority”. The spider leg is a single beam or fascia that “fascia stretches far beyond the edge of the roof at a major corner and turns down the reach the ground”. By displacing the corners of rooms and “in some cases the very structure of the house such normally stabilising architectural elements are indeterminately inside and outside at the same time.”

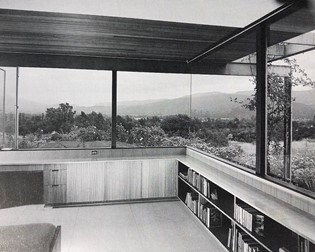

One of the most celebrated features of his architecture is the corner where one glass plane meets the other. At this corner the floor to ceiling glass meets at a mitred edge to produce a glazed environment of intense spatial ambiguity. Here there is a distinct oscillation between opacity and transparency, interiority and exteriority, solidity and fluidity and it generates perceptual confusion. Here the “glass and frame perform to both produce and suppress the edge of the house.” In the Moore House (1952) “the corner provided [Mrs. Moore] with a sense of the inter-relation of Nature without and living within that could do nothing less than eliminate the depression which we feel. She felt this interrelationship especially on a misty gloomy day, in other words when the house was at its most moody and when she turned to the window to get out, to enter its distant view over the far landscape and to join what she called the ‘mystery over the mountains’.” Neutra saw this corner as the precise moment where instabilities and uncertainties collect and where desires, both psychic and organic are projected.

Our human psychology, Neutra recognised, comes from our human birthplace of "the primeval forest or the grassland of prairie and pampas," but has now become 90% man-made. Nonetheless, we still feel most comfortable in places that replicate the patterns of our ancient birthplaces. One of the most potent is that of "prospect and refuge." As Barbara Lamprecht explains,

“prospect,” meaning looking out above your surroundings from a commanding position … afforded by glass walls. In contrast, the kitchen and the bedroom/dressing area, with their walls of warm mahogany, create the counterweight to prospect in the quality called “refuge,” or shelter, or what Gaston Bachelard called the cave. Both prospect and refuge are necessary to us.

Bothe qualities, of course, would have been physically necessary when subject to potential attack by wild animals, or other humans! Now they are just as necessary psychically.

Those manipulations of corners, opening them up in contrast to a deep and sheltering corner opposite, is just one of the patterns Neutra built into his houses that recognised this deep psychological need. And this strong contrast between the deep sheltering "cave" set off against the opportunities for prospect made the whole space appear larger, and more active.

Neutra delivered a small space that feels expansive, not cramped, because it has an effect beyond its four walls. As he often said, his goal with small houses was to “stretch space” ...

So how well did all this work in practice? Freed summarises it as seeing its success from the few failures:

One of his clients, Mrs. Logar, wrote to Neutra in 1956 (just four years after building the home in Granada Hills California) saying that she and her husband wished to sell their house. She states, “it looks messy all the time and there is no place to hide things away. We are entirely exposed to view from all sides. This is just about right for some executive and his wife. I think I prefer to live in an old hidden away place for a couple of years to clear my thoughts.”Mrs. Logar was exhibiting one of the common criticisms of Neutra’s homes: the feeling of vulnerability and extreme exposure that accompanied living in the glass house.

However this complaint is the home’s very success, not failure. Based on the Freudian understanding of empathy, which is defined as “an unconscious defense against internal impulses… to projection onto an inanimate object… into a defensive transfer of feelings onto another subject” it can be inferred that those who are experiencing these fears of exposure and vulnerability are actually experiencing their unconscious repressions becoming conscious. In the Freudian manner Neutra has brought to light what they have repressed since childhood- their fear of exposure and vulnerability- in order to overcome these fears and be cured of their neurosis.

Mrs. Rourke, contrary to Mrs. Logar’s opinion, “argued that Neutra had given them a new living experience [and she] could think of only one word to describe the way she felt about it: Liberation.”While Mrs. Logar failed to overcome her phobia, Mrs. Rourke’s statement suggests that she was able to embrace the vulnerability tied to exposure from all sides at all times and was rewarded with a improved quality of life. The “improperly bounded environments of these houses permitted psychoanalysis to be everywhere and nowhere at the same time. The houses’ naturalising materials, blurred structure, and camouflaged glass are both in the open and deliberately evade the gaze, enabling their therapeutic actions to be everywhere while out of view.”

Understanding a building's enclosure in terms of patterns like "connecting with nature" and "prospect and refuge" allows us to understand how we can shape our houses today to meet the psychological needs of today's inhabitants. As Abigail Freed concludes:

This type of architecture is always a success if it at the very least helps those struggling feel as through they are helped. What is the harm if it relieves only the inner anxieties of some? Critics may claim it is “all in their head”, but that is the very basis of emotion -- we all exist in our own heads.Agree or not, perhaps the most important thing to take away is that our psychological facts and requirements are just as important to the design of our houses as our physiological needs, or the house's structural demands. They are all facts of existence that we must take into account in our designs.

When we do, successfully, they can be a curative.

No comments:

Post a Comment