|

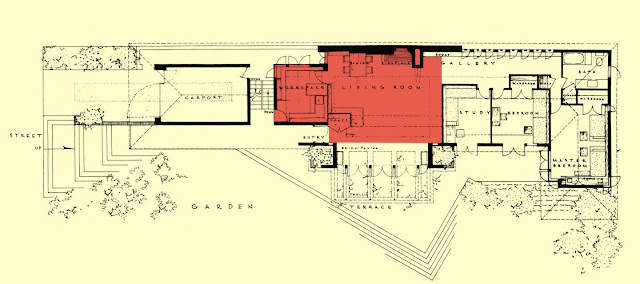

| Floor Plan, Malcolm Willey house, 1933, by Frank Lloyd Wright (with then-radical integration of kitchen and living spaces highlighted) |

What is the ideal relationship of architect to client?

Architects Charles & Ray Eames had a somewhat similar approach, based upon a conversation with Eero Saarinen on the subject of the Guest/Host Relationship, saying:

Building upon that idea, designer Steve Sikora sees designer and client as "dancers in a complicated tango of wills"--the better clients helping produce a greater architectural response.

REF:

Quotes from:

I like to quote architect Bruce Goff, who said he "liked to do what they [his clients] would do if they were a good architect." Each client being as unique as every individual, Goff would devise a unique house for every client, spending as much time discovering who they really were, in order to discover how best to make their home best fit them -- as if they had been able to produce it out of themselves.

Architects Charles & Ray Eames had a somewhat similar approach, based upon a conversation with Eero Saarinen on the subject of the Guest/Host Relationship, saying:

One of the things we hit upon was the quality of a host. That is, the role of the architect, or the designer, is that of a very good, thoughtful host, all of whose energy goes into trying to anticipate the needs of his guests—those who enter the building and use the objects in it. We decided that this was an essential ingredient in the design of a building or a useful object.I think that's a great way to think about it.

Building upon that idea, designer Steve Sikora sees designer and client as "dancers in a complicated tango of wills"--the better clients helping produce a greater architectural response.

My partner, Lynette and I shared the mixed blessing of leading a design and branding firm for over 30 years. One of the lessons you take from that, is the understanding that the quality of your work is significantly determined by the quality of the clients you work with. Notice, I said work with, rather than work for. When a designer is able to ally as equal partner with a client of vision and courage, it creates fertile ground for optimal results in every endeavour. Doubtless, in our practice, our greatest achievements would not have been, were it not for the engagement, faith and occasional challenges presented by our clients.Applying this to Frank Lloyd Wright's highly innovative 1933 Willey House (plan, above), about which Sikora (as owner) writes frequently, not least about its dramatic impact on modern domestic design:

In the case of the Willey House, Nancy presented Wright with enough constructive resistance to lift her dance partner above the prevailing paradigms of domestic architecture.Wright's approach demands a demanding but open client.

As John Sergeant observed, “The relationship between client and architect was for Wright a thing of joint intent.” To achieve clear focus and gain permission, even “In large projects he always sought out one person and never a committee, to represent the client.” That, as they say, is easier said than done, but it was a prerequisite that governed his creative and persuasive processes...

When [his son] John Lloyd Wright considered a career in architecture, his father gave him this advice, “You’ve got to have guts to be an architect! People will come to you and tell you what they want, and you will have to give them what they need.” “Don’t you take the wants of the client into consideration?” John asked. “If you consider the house first, you will supply the needs of the client. The wants change from day to day, but a house must embody the needs of those who live in it. The architect must be aware of those needs, the client seldom is. An architect must have the courage to turn away a commission even if he is hungry if his work will not represent the highest ideals….Think it over, John: to be an architect is no light matter.”The Willey House was a small masterpiece that helped re-set Wright's residential thinking for the rest his career; a new form that flourished in the creative tension between a responsive architectural genius and a demanding yet sympathetic client.

Consider this, a client will typically select an architect based upon their past artistic expressions. Nancy Willey was certainly a case in point. Yet the same client will judge their architect by how well their needs are met, once the design is implemented. This too, is evident in the correspondence between Nancy Willey and Frank Lloyd Wright. In her initial letter she asked “What do you think are the chances of my being able to have a – creation of art?” She repeatedly expressed wanting to follow his instructions to the letter. But when pressed into a corner, having to decide between high art and pragmatism, she was willing to fight for what she knew she needed and could afford. On November 17, 1933 frustrated with construction bids coming in at two times over budget on scheme 1, she penned a terse letter to Wright. In it she wrote, “I do not want a seventeen thousand dollar house even at twelve or ten thousand dollars. I want an eight to ten thousand dollar house at eight to ten thousand dollars. Can I have it?” We have Nancy’s red line and assertive pushback to thank, for what inspired Wright to cast aside his initial ideas and ultimately seek a more appropriate solution. Once the water broke, something new and wonderful was born, relieving the tension between clients and architect. From that point forward, in full alignment, both parties strove to advance the project with renewed enthusiasm. In Nancy’s own words from her Oral History interview with Indira Berndtson “…and how he responded, once he accepted it!!Dance partners -- host and guest -- interpreter of true needs -- discover of a client's inner person. The good architect is all of these in one. And the ideal client is the ideal reciprocal to all these. But as Steve Sikora summarises, there is one quality above all that is required of a good client:

I had the chance to meet a life-long graphic design hero of mine, Milton Glaser. It was at a conference in New Orleans, where we both presented. An idea from his presentation became indelibly inscribed into my memory. While discussing his long career, Milton spoke about clients. He said, “I could never work for anyone who I did not have a genuine affection for.” His words were profound, because they implied two things; he could only do his best work for people he liked, but also, in a professional context, he gave permission for designers to understand, appreciate and embrace clients as fellow humans, even potential friends. He believed in collapsing formal, professional barriers. I instantly related his sentiment to my own client relationships.And I, I hope, to mine.

REF:

Quotes from:

- Willey House Stories Part 5 – The Best of Clients, by Steve Sikora - at the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation website

- The Guest/Host Relationship - at the Eames Office official site

No comments:

Post a Comment