NB: This 3d hypermodel linked above uses Archicad BIMX technology. Click here for instructions to make your exploration of the model easier and more enjoyable.

Monday, November 19, 2018

Verandah Addition, Mt Eden

NB: This 3d hypermodel linked above uses Archicad BIMX technology. Click here for instructions to make your exploration of the model easier and more enjoyable.

Thursday, November 15, 2018

Carport Addition, Mt Eden

NB: This 3d hypermodel linked above uses Archicad BIMX technology. Click here for instructions to make your exploration of the model more enjoyable.

.

Wednesday, October 24, 2018

QUOTE: "The complete architect is master of the elements: earth, air, fire, light, and water. Space, motion, and gravitation are is palette: the sun his brush. His concern is the heart of humanity."

"The complete architect is master of the elements: earth, air, fire, light, and water. Space, motion, and gravitation are is palette: the sun his brush. His concern is the heart of humanity." ~ Frank Lloyd Wright, 1949[Hat tip to and photo from the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation]

.

Thursday, October 04, 2018

Did you know you can explore the online 'hypermodel' of a Mt Eden house we're working on at the moment?

See how you go... (I'm told folk used to gaming will fly through the documentation!) But you could make your exploration easier by going full-screen, and then clicking on the index at the top left of the screen.

Enjoy...

NB: This 3d hypermodel linked above uses Archicad BIMX technology. Click here for more detailed instructions to make your exploration of the model easier and more enjoyable.

.

Wednesday, August 15, 2018

QotD: “It is almost possible to say that there is a mathematical relationship between the beauty of his surroundings and the activity of the child; he will make discoveries rather more voluntarily in a gracious setting than in an ugly one...”

“It is almost possible to say that there is a mathematical relationship between the beauty of his surroundings and the activity of the child; he will make discoveries rather more voluntarily in a gracious setting than in an ugly one...”~ Dr Maria Montessori, founder of the Montessori educational system

.

Saturday, July 14, 2018

Q: How long will my building consent take?

There are several questions I get asked more than any other from clients, including "How much will this cost?", "When will my drawings be ready?", and "What's a ceiling deck?"

But if there's one question I get more than any other, it's "How long will council take to issue my building consent?" Which is also the most difficult question to answer.

You'd think it would be easy -- after all, the Building Act requires council by law to issue a building consent within 20 working days of the consent application being lodged. So does that provide a useful guide? Not at all.

You see, instead of applying their ingenuity to getting building consents out the door, overworked councils have instead devised many ingenious ways to get around this law that appears to hang a ticking clock around their heads. Most of them involve ways to stop that clock ticking.

Some councils, for example, will take a week or two to determine that your consent has indeed been formally lodged. Back in the days when we used to take hard copies into council offices, a meeting there would determine that you had indeed supplied all the necessary documentation, and the council's clock would then start ticking immediately. Today, it's different. First, the amount of paperwork we need to supply in lodging for a consent is a whole lot more than it ever was, so ti takes a whole lot longer to check it's all there. And because submissions are now online, it's up to council themselves to decide when the clock starts. Can you guess what sort of incentive they have to start that clock quickly?

So that's their first. It's annoying, especially when you're impatient to start. But it's nowhere near as maddening as what happens next.

Taking time to decide when your consent is lodged delays the clock starting. What happens next gives council a way to stop the clock ticking. What happens next is the result of another loophole in the Building Act -- that every time the council asks us for more information their clock stops again. And it doesn't start again until they have decided you've supplied what they're after!

Can you guess what incentives that sets up? Yes, you've guessed it: a huge incentive to ask any and every question they can dream up about extra information that for the most part is completely useless. "Please provide details of the stair fixing on the lower landing." "Please provide the make and model of the shower." "Please indicate the finish of the bathroom cabinet."

In recent months I've been asked about the colour of bedroom carpets (accompanied by a calculation to show they're bright enough); the normal process by which to pour a concrete footing in engineered soil (about which every apprentice could tell you); to abandon approved details because the territorial authority has decided they don't like them (replaced with those council themselves like but which look decidedly dodgy to me); the acoustics of polystyrene sheets (that are not being used for acoustic purposes); to resupply calculations and statements that the processor has already received, but lost; to explain why handrails are not required on steps with fewer than two treads; and how an opening window into an open lightwell allows light and air into a room; to draw up a list of a project's "construction and demolition hazards"; to provide mechanical ventilation rates for areas we've shown will use natural ventilation (i.e., windows); to draw up simple diagrams because processors are unable to read fairly standard plans; to confirm the use of smoke detectors (when they've already been clearly placed and labelled on drawings) -- just some examples of many, many, many recent Requests from processors, all of which have wasted my time and theirs, unnecessarily dragging out the consenting process, and all at the time and expense of clients who were once very eager to build.

The simplest RFI responses are to tell the questioner where precisely in the document set they can find the answer to their question, already addressed. And the stupidest I've ever received, "Please provide details of the basin splashback" -- this because the poor fellow couldn't find anything else in the drawing set about which to ask a question!

This is officially called a "Request for Further Information," or RFI, and they are the bane of every designer's and architect's life; instead of getting on with lodging our next job, we're instead answering stupid questions about our last one -- and all just to give our friends at council time to get on with what we'd all like them to be doing instead of writing letters to us!

This doesn't mean that every question isn't justified (when so much paperwork is required it's not surprising there might be some things missing!) But it does mean that the incentive on each of us designers is to supply an ever-increasing amount of paper in order to preclude any questions being asked -- giving council even more paper to process as well! -- while the incentive on council processors is not so much to process as to burrow through looking for questions. Which means, these days, that the process often feels less about being a designer than it is about being a lawyer, explaining the Building Code clauses to the processor at the other end of an email.So, how long does it all take then? Or, as my clients so frequently ask me: "How long will my building consent take?" The simplest answer is that it won't be 20 working days. Generally it's only at 19 working days that we receive our first RFI. Yes, I did once manage to get a drainage consent while I was standing there in the council offices. But that was many years ago. In general now, the easiest answer is to give clients a range: which is somewhere between six weeks and six months. The quickest I've seen one come out in recent years is 10 days. The longest was 10 months. (And the most maddening thing was that there was nothing substantially different about those two projects to justify that difference!)

So there's just no way to give a good answer, I'm afraid.

That said, it can be easier if council are processing over the Xmas break, because over the Xmas period there are very few official legally gazetted working days, so that council processors who are working through -- which can happen sometimes, when council are busy -- can actually process instead of delay. So sometimes it can make a difference getting lodged before Christmas.

And we do have to remember that we're building something for you to enjoy over many years. At the end of the day, when all the problems have been solved and your house is built and you're sitting there enjoying it all with your family, who really remembers an extra week or two at this point except those of us who have fought to get your paperwork over the line?

.

Thursday, July 12, 2018

Recent Project: Bank Conversion

Another project I’ve been working on recently is this one: a mostly interior conversion project (with some delicious exterior decoration to come!) converting an elegant mid-century downtown commercial building into a new life as a funky urban pad for a small family that works from home.

Thursday, May 17, 2018

What is the ideal relationship of architect to client?

|

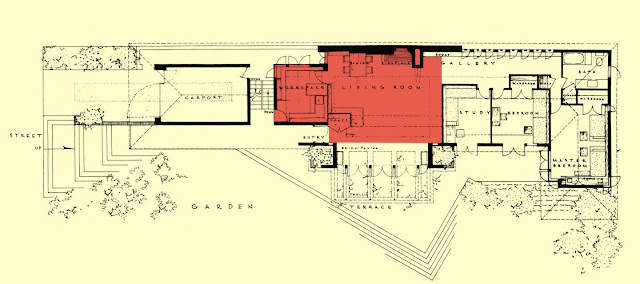

| Floor Plan, Malcolm Willey house, 1933, by Frank Lloyd Wright (with then-radical integration of kitchen and living spaces highlighted) |

Architects Charles & Ray Eames had a somewhat similar approach, based upon a conversation with Eero Saarinen on the subject of the Guest/Host Relationship, saying:

One of the things we hit upon was the quality of a host. That is, the role of the architect, or the designer, is that of a very good, thoughtful host, all of whose energy goes into trying to anticipate the needs of his guests—those who enter the building and use the objects in it. We decided that this was an essential ingredient in the design of a building or a useful object.I think that's a great way to think about it.

Building upon that idea, designer Steve Sikora sees designer and client as "dancers in a complicated tango of wills"--the better clients helping produce a greater architectural response.

My partner, Lynette and I shared the mixed blessing of leading a design and branding firm for over 30 years. One of the lessons you take from that, is the understanding that the quality of your work is significantly determined by the quality of the clients you work with. Notice, I said work with, rather than work for. When a designer is able to ally as equal partner with a client of vision and courage, it creates fertile ground for optimal results in every endeavour. Doubtless, in our practice, our greatest achievements would not have been, were it not for the engagement, faith and occasional challenges presented by our clients.Applying this to Frank Lloyd Wright's highly innovative 1933 Willey House (plan, above), about which Sikora (as owner) writes frequently, not least about its dramatic impact on modern domestic design:

In the case of the Willey House, Nancy presented Wright with enough constructive resistance to lift her dance partner above the prevailing paradigms of domestic architecture.Wright's approach demands a demanding but open client.

As John Sergeant observed, “The relationship between client and architect was for Wright a thing of joint intent.” To achieve clear focus and gain permission, even “In large projects he always sought out one person and never a committee, to represent the client.” That, as they say, is easier said than done, but it was a prerequisite that governed his creative and persuasive processes...

When [his son] John Lloyd Wright considered a career in architecture, his father gave him this advice, “You’ve got to have guts to be an architect! People will come to you and tell you what they want, and you will have to give them what they need.” “Don’t you take the wants of the client into consideration?” John asked. “If you consider the house first, you will supply the needs of the client. The wants change from day to day, but a house must embody the needs of those who live in it. The architect must be aware of those needs, the client seldom is. An architect must have the courage to turn away a commission even if he is hungry if his work will not represent the highest ideals….Think it over, John: to be an architect is no light matter.”The Willey House was a small masterpiece that helped re-set Wright's residential thinking for the rest his career; a new form that flourished in the creative tension between a responsive architectural genius and a demanding yet sympathetic client.

Consider this, a client will typically select an architect based upon their past artistic expressions. Nancy Willey was certainly a case in point. Yet the same client will judge their architect by how well their needs are met, once the design is implemented. This too, is evident in the correspondence between Nancy Willey and Frank Lloyd Wright. In her initial letter she asked “What do you think are the chances of my being able to have a – creation of art?” She repeatedly expressed wanting to follow his instructions to the letter. But when pressed into a corner, having to decide between high art and pragmatism, she was willing to fight for what she knew she needed and could afford. On November 17, 1933 frustrated with construction bids coming in at two times over budget on scheme 1, she penned a terse letter to Wright. In it she wrote, “I do not want a seventeen thousand dollar house even at twelve or ten thousand dollars. I want an eight to ten thousand dollar house at eight to ten thousand dollars. Can I have it?” We have Nancy’s red line and assertive pushback to thank, for what inspired Wright to cast aside his initial ideas and ultimately seek a more appropriate solution. Once the water broke, something new and wonderful was born, relieving the tension between clients and architect. From that point forward, in full alignment, both parties strove to advance the project with renewed enthusiasm. In Nancy’s own words from her Oral History interview with Indira Berndtson “…and how he responded, once he accepted it!!Dance partners -- host and guest -- interpreter of true needs -- discover of a client's inner person. The good architect is all of these in one. And the ideal client is the ideal reciprocal to all these. But as Steve Sikora summarises, there is one quality above all that is required of a good client:

I had the chance to meet a life-long graphic design hero of mine, Milton Glaser. It was at a conference in New Orleans, where we both presented. An idea from his presentation became indelibly inscribed into my memory. While discussing his long career, Milton spoke about clients. He said, “I could never work for anyone who I did not have a genuine affection for.” His words were profound, because they implied two things; he could only do his best work for people he liked, but also, in a professional context, he gave permission for designers to understand, appreciate and embrace clients as fellow humans, even potential friends. He believed in collapsing formal, professional barriers. I instantly related his sentiment to my own client relationships.And I, I hope, to mine.

REF:

Quotes from:

- Willey House Stories Part 5 – The Best of Clients, by Steve Sikora - at the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation website

- The Guest/Host Relationship - at the Eames Office official site

Saturday, April 28, 2018

"Man, too, is no less a feature of the landscape than the rocks, trees, bears or bees of that nature to which he owes his being.”

“Man takes a positive hand in creation whenever he puts a building upon the earth beneath the sun. If he has any birthright at all, it must consist in this, that he, too, is no less a feature of the landscape than the rocks, trees, bears or bees of that nature to which he owes his being.”

~ Frank Lloyd Wright, 1937

Friday, April 27, 2018

Getting a flower out of the system instead of a weed

That's where the light gets in."

~ Leonard Cohen

Weeds abound. Weeds can be found in every suburb, and every magazine. Weeds are what we get out of the system when we all try least hardest. But why live in a weed for twenty years or more just because the system makes building and buying weeds easier than it is to produce a flower? And why go to the effort of building yourself if the final result of all that angst and energy is just another weed.

We use this frequently as a slogan -- getting a flower out of the system instead of a weed -- but it's a slogan that we really mean. The weeds the system throws up don't interest us. The flowers we can grow out of it do. Immensely.

This is what we do every day here at Organon Architecture: work to get a flower out of the system instead of a weed. With the system now more grotesque now than it's ever been, it's never been more important.

Thursday, April 26, 2018

"'Jumping through hoops' is pushing up building costs" [updated]

Fire engineers are accusing councils of making illegal demands on them that are inflating building costs by thousands of dollars... "I've become totally used to how bad it is, I'm sort of numb to it, it's just a bureaucratic nightmare right now," Wellington fire engineer Kenneth Crawford of Pacific Consultants said. "We've got so many demands coming from council ... it's pushed up costs, it's creating months and months of delays in obtaining a building consent, and none of this is actually really improving safety." A fire design on a small warehouse in 2013 that might have cost $1200 to $1500 was now costing at least $4000, and up to $20,000, he said.Sadly, as anyone who's recently endured the consent process could tell you, it's not confined to fire engineers.

The Building Act requires council to process Building Consent applications within twenty working days of being lodged. Council have two dodges to get around this. The first is to set up a process to decide when the application has been successfully lodged. This can easily take two weeks, with no work at all done n processing. And the second -- based on he principle that "the clock stops" when questions about the project are asked -- is to ask as many silly questions as council processors can think of, all of them calculated to show down the processing and frustrate client, consultants and designers. [This 2013 table from Christchurch will give you some idea of the time 'saved' in this way.]

In recent months, for example, and like every regular applicant for building consents, I've spent many, many hours replying to council's Requests for Further Information (RFIs). These days it's often less about being a designer than it is about being a lawyer, explaining the building code clauses to the processor at the other end of an email.

The simplest RFI responses are to tell the questioner where precisely in the document set they can find the answer to their question, already addressed. But in recent months it's been getting worse. Among other things, in order to keep things moving I've been required to tell council the make and model of a shower and the finish of a bathroom cabinet; the colour of bedroom carpets (accompanied by a calculation to show they're bright enough); the normal process by which to pour a concrete footing in engineered soil, to abandon approved details because the territorial authority has decided they don't like them, and to replace them with those they've now decided they do; to discuss the acoustics of polystyrene sheets (that are not being used for acoustic purposes); to resupply calculations and statements that the processor has already received, but lost; to explain why handrails are not required on steps with fewer than two treads, and how an opening window into an open lightwell allows light and air into a room; to draw up a list of a project's "construction and demolition hazards"; to provide mechanical ventilation rates for areas we've shown will use natural ventilation; to draw up simple diagrams because processors are unable to read fairly standard plans; to confirm the use of smoke detectors (when they've already been clearly placed and labelled on drawings); and (in the absence of council finding anything else to ask about) to draw a detail of a bathroom splashback -- just some examples of recent Requests from processors, all of which have wasted my time and theirs, unnecessarily dragging out the consenting process, and all at the time and expense of clients who were once very eager to build.

I'm sure you can all add your own list of examples. (And please do!)

I'm sure you can all add your own list of examples. (And please do!)This process is often worse when councils sublet the processing to a consultant, whose motivation is then to spin out the questions in order to pad the bill. This can work out very nicely for the very average consultant, but very poorly for clients who have budgets and builders trying to programme in their work.

And all this of course is in addition to the truckload of documentation, in triplicate, that has to be supplied just to 'get in the door' to make that original application, the sheer volume of which in itself delays the processing and all but guarantees inconsistencies will appear in the document set. By way of illustration, I may be renovating a house built in the 1920s, of a style that is still very popular, the original drawings of which are on one A4 page with another smaller page containing what might be called the specification -- which might say little more than 'use nails.' And this 'document set' was probably drawn up by either the builder or owner. Yet to renovate that house now I will need documentation of around 24 A1 pages, and A4 specifications and accompanying documentation of around a thousand. And neither builder nor owner will be allowed to prepare those documents unless they have been previously Licensed by a government department to do so.

Every year it's been getting worse, without making the houses any better. In 2007, for instance -- aware that things were becoming more complicated in this new age of Licensing, Producer Statements and Memoranda/Certificates of Design Work-- the Department of Building and Housing produced a Guide to Applying for a Building Consent. It was a 44 pages long. The second edition appeared just three years later. It was already 62 pages long. None has appeared since: perhaps because no-one would have the time to read a document as long as it would now need to be. Crikey, these days it takes well over a day just to complete the application forms and processes to apply for a consent, and more than a day for every response thereafter. All of it time wasted.

Every consultant will tell you similar stories, and not just fire engineers.

Yes, 'jumping through hoops' is pushing up building costs, and has been for some time.

Until or unless the Building Act is amended to remove risk from council -- and their ratepayers -- the hoops (and costs) are going to get worse, not better.

UPDATE: Further comment this morning on the mis-apportioning of risk (Friday 27):

From Radio NZ the morning after:

The impact of everyone trying to pass all the risk on, was it was getting harder to build anything at a time of housing shortages, the Property Council's chief executive Connal Townsend said..

"The overall public policy setting of how the heck we manage risk, is completely out of whack," he said.

"We've just got people passing the ticking timebomb from one hand to another and blaming each other. It's pointless.

"We have to tackle the way risk is allocated and the fact that councils are left carrying the liability is just hopeless, absolutely hopeless."

The previous government tried hard to fix the problem [cough, cough - Ed.] but couldn't, and it was urgent this government confront it, he said.

The risk issue was a perverse result of building laws being overhauled in 2004 to combat the leaky building crisis.

Lawyers, including the Law Commission in a 2014 report, have since then resisted changing the way liability is doled out.

"The net effect of our joint-and-several system is that councils are left carrying the can," Mr Townsend said.

"This story with the fire engineers, all they've done is blown the whistle on a ridiculous problem that has to be solved."

Friday, January 12, 2018

Q: What is a house?

“The house is a machine for living.”

~ a banality from the very banal Le Corbusier

“Oh yes, young man; consider that a house is a machine in which to live, but by the same token the heart is a suction pump. Sentient man begins where that concept of the heart ends. “Consider that a house is a machine in which to live, but architecture begins where that concept of the house ends. All life is machinery in a rudimentary Sense, and yet machinery is the life of nothing. Machinery is machinery only because of life.”

~ Frank Lloyd Wright, from his lecture ‘To the Young Man in Architecture'

"A house is not a machine to live in. It is the shell of man — his extension, his release, his spiritual emanation. Not only its visual harmony but its organisation as a whole, the whole work combined together, make it human in the most profound sense… The poverty of modern architecture stems from the atrophy of sensuality.”

~ architect Eileen Gray, designer of the house that Le Corbusier could never have designed, but nonetheless fell in love with

“A house is not an object but a universe we construct for ourselves – not a garage where we park ourselves.”

~ architect Claude Megson, on 'making a home for man'