Tuesday, October 07, 2025

"Nature Near"

Monday, September 29, 2025

Five architectural "must-haves"

I have to confess that I get very little out of TV architecture programmes. The "Grand" of the design(s) too quickly becomes Grandomania.

But this snippet of five architectural "must-haves" that just popped up on Youtube has some very good points. Architect Steven

Harris calls them his "non-negotiables," and he talks about them here in the context of his own house. It's not about their house's style—which you may or may not admire—it's about some simple principles on which it's based.

I've pasted the tips below, with my comments underneath each:

No. 1: Refine the entry experience: The first of architect Steven Harris’ 5 non-negotiables when designing his own home is determining the sense of approach. Rather than abrupt thresholds, the journey into the house is articulated as a gradual transition. From the initial glimpse across a golf course to the curved courtyard entry, each spatial reveal is calibrated. Inside, a stepped sitting room draws the eye to distant mountain views. This sequence generates anticipation, framing experience through a procession that’s both psychological and physical.

It's a truism to say that first impressions count. Because they do. As marketers say, "There's no second chance to make that good first impression"—or to be introduced to the landscape a better way.

So the way you (and your guests) are introduced to your home and the landscape beyond is critical, since it will leave a lingering impression. Most important here is to hold the important view until it achieves its maximum impact, so it will resonate deeply. To help this, use containment and release: masking the view until the right time, containing the space at the entrance, so that the view explodes once you're place into it.

No. 2: Create a strong link to nature: A seamless relationship between indoors and out is integral to the home, and the landscape design by David Kelly of RRP enables an easy flow between each domain. The architecture dissolves boundaries with landscaped berms and exterior gathering spaces that extend the footprint into the garden. At this site, the feeling is less like a house on a golf course and more like a pavilion in a park. By designing the contours of the land, the team create depth and intimacy, reinforcing a connection to the broader terrain while encouraging everyday interaction with nature.

This is crucial. Human physiological needs are as important in a building as their structure. And as numerous researchers have confirmed, “The inherent human inclination to affiliate with nature, even in the modern world, continues to be critical to people’s physical and mental health and wellbeing.” This intense human need to have ‘nature near,’ as architect Richard Neutra explained — to interweave structure and terrain — is not just a frivolous extra in our buildings, but a vital need.

No. 3: Consider the flow of movement: Flow and circulation are the third non-negotiable. Architect Steven Harris’ 5 non-negotiables when designing his own home emphasise the importance of reducing unused space. Hallways are minimal or absent, with rooms leading into one another in a sequence that promotes daily engagement. The guestrooms are detached, accessed through the garden, allowing the house to function as a single-bedroom retreat when unoccupied by visitors. This planning prioritises experience over expedience, ensuring all areas of the home are lived in and appreciated.

Space that flow make a more comfortable place. In the best houses, you don't spend wasted minutes crossing and re-crossing hallways—you find yourself in the best places as the day progresses. Spaces interlink and interlock, sharing space and making the most of it. Every square metre used in a hallway is a wasted square metre. So use them sparingly.

No. 4: Understand your clients’ lifestyle: Fourth is programmatic clarity. Spaces are designed to reflect actual living patterns rather than ideals. Rooms often serve dual functions, like dining areas that double as workspaces or libraries. Television is integrated into the living room to ensure its frequent use. This principle stems from understanding daily rituals and designing around them. Architect Steven Harris’ 5 non-negotiables when designing his own home place emphasis on functionality that doesn’t sacrifice sophistication.

It's absolutely essential to know what spaces your clients use most often, and when. Which means you must know in detail how they actually live. So do ask them to list what they're doing the house each day, and what time of day, and for how long. "The best way for a client to really think about what they need for a house," they say, "is to think about the process of each day and how they live it." Very true.

Not in agreement there with the television however [2], since reducing its frequent use is more important (and smaller devices mean the "family television" now gets less use anyway). But the point is a good one: design for the way you live, not the way a magazine or TV show thinks that you should. Build in the daily rituals that give your life meaning. (And do be open to lettin the architecture suggest better ways to live.)

The final principle centres on scale and proportion. Rather than equating size with importance, the design treats intimacy as a metric of success. Volumes are generous without being overwhelming, with seating arranged to foster ease of conversation. The dressing room and bathroom are given as much attention as the bedroom itself.

This perhaps is most important. There's a luxury in good design in that you're not making spaces bigger: you're making them just the right size. There are important human dimensions that we must build in, and fail at our peril. A conversation space, for instance, calls for a 3m radius from eyeball to eyeball. Make it bigger or smaller, and we're making a wasted space. Build in these human dimensions, and we're making a home that just feels right.

* * * *

There are other "non-negotiables" we all might have, but these are a good start.

PS: Looking at Harris's beautiful home, one commenter quipped that the sixth non-negotiable would be an unlimited budget. Which is funny to say, but not truly necessary to have: because none of these elements require an extensive budget; they simply require thought. As Steven Harris says, if you don't get these things right—most especially the human dimensions—then "all the fancy materials in the western world aren't going to help."

It really is all about thinking it through.

* * * *

[1] Stephen Kellert & Elizabeth Calabrese, The Practice of Biophilic Design (2015): 3

[2] Of course, their point here is that so many homes now offer a "media room" that takes folk away from the main living space on which you've lavished so much care. Now, clearly Americans watch too much television anyway, but I do think there's a good argument for the media room.When you just want to watch "the news" or a TV series, then a smaller screen is fine, and can be in lounge or dining space or wherever. But when a film director relies on a big screen (as any director should) or a sports broadcast demands much bigger screen real estate, then it's good to repair to a place dedicated to that function of enjoying the film (or the sports broadcast) on a dedicated big screen.

Wednesday, March 26, 2025

ARCHITECTURAL MINI-TUTORIAL: Soft Geometry

Here's a very simple principle to bring into your kitchen: corners can hurt.

Ouch!

The solution is simple: something called Soft Geometry, instead of hard.

Grey's experience with the Alexander Technique led him to study how body movement is affected by peripheral vision, which, surprisingly, turns out to be another source of muscle tension. When your eyes sense sharp corners on the edge of your path, they activate a stress response to ensure that you avoid hitting anything. This makes you more tense.

To counteract this and make the time spent in the kitchen more relaxing, Grey developed what he calls "soft geometry." His counters have round edges; his islands and the cabinetry below them are circular or elliptically shaped, while the counters and cabinetry opposite them are often concave. He also likes free-standing, floor-to-ceiling cylinder-shaped cabinets for storing large pots and pans. All these unusual shapes make the space feel more playful, which is also relaxing.

The unusual shapes would seem to require a bigger area for a kitchen, but Grey said the opposite is true. With a concave-shaped kitchen, you can get more cabinets and appliances into a smaller space, while freeing up more floor area so that two or more people can work at the same time.

I want to make environments that make you feel good, that foster well-being [says Grey]. I started working with neuroscientists eight years ago – in particular John Zeisel – which validated a lot of the things I’d been doing with emotionally intelligent design. I also wanted to apply the science of happiness to kitchens , which was inspired by Sir Richard Layard’s book, 'Happiness: Lessons from a New Science.' He noted people were happiest between 5-9pm when they are either in the pub or their kitchen. So the question for the kitchen designer is, how do we enhance that?We need to have a central island where the hob is placed so the cook can face the room with a raised height bar for food serving and for leaning against. Visitors can then sit or perch and chat with the cook who can keep eye contact with the entire room. You need also different level work surfaces for small children and secondary work stations and plenty of table space so that lots of different activities can take place simultaneously.

His suggestion to make that eye contact easier is a central island in the kitchen, but one with curved corners, rather than angles and sharp edges.

"Anything that is in your peripheral vision demands more brain action. And something that is sharp can cause anxiety, however subliminal, because we are aware it's something we should avoid bumping into, as it could hurt.

"There's a practical benefit, too, because by using rounded corners for furniture you can take less space for walk-through areas.

Movements will be more relaxed, as subconsciously you won't feel the need to allow more room as you pass fittings."

While acres of counter space may look impressive, it's not what we need emotionally, says Grey, who believes we are more relaxed when we have less choice and more compact spaces to work within.

Thursday, January 11, 2024

How to begin creating Organic Architecture ...

|

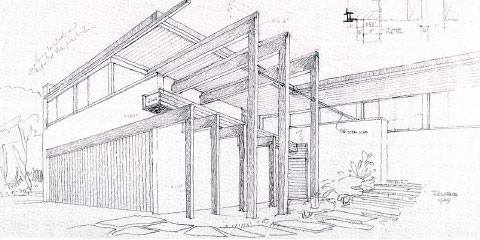

| 'Rasmussen Residence,' 2003, by architect James Schildroth |

Organic architecture is not about assembling boxes and coating them with candy floss. For that, read your latest glossy "architecture" magazine or Instagram page -- or watch the latest episode of Grand Designs. Former Frank Lloyd Wright apprentice James Walter Schildroth explains that to design organic architecture, you need to start not from without but from within. Why? Because, as he says, "This is architecture not sculpture art. What is important is the human being who will use the space." Organic architecture puts human beings in relation to the world beyond. "Space never confines. Space is always in relation to the beyond."

Here's how he learned to design for human beings this way apprenticing at Frank Lloyd Wright's practice...

Learning to design at Taliesin

By James Walter Schildroth, Architect

When I arrived at Taliesin in September of 1959, I had good drafting skills and had taken three years of mechanical drawing in high school and one year in junior college. I had been reading several of Mr. Wright’s book including A Testament and the The Natural House. I had been mentored by Will Willsey, Architect and Taliesin apprentice in 1954-55. Will, had introduced me to the use of the ‘unit system’ and I was working out designs using the four-foot square unit. I did not understand how to get an original design. I was just emulating the Wrightian design and making a few of my own changes.

I wanted to learn how to create original form and ideas. This why I had come to Taliesin and I was determined to learn and would stay as-long-as it took to know if I could do it or not.

The idea for an original design was the goal. How did Mr. Wright and others do it?

Organic is “of the thing and not something applied for the outside.” It is not copied or made to look like something that exists. I could make a logical floor plan but the plan was not the idea, it was just a floor plan. The idea must come from some other place, but where and how?

Breaking the box was much talked about.

Someone explained that if one was making a floor plan of a 120 square-metre house, they could draw a rectangle 10m x 12m and fit all the rooms inside. This was not the ‘Organic Way.’ The Organic way, was to let the individual areas of the house be put in a relationship to the site as well as in a relationship to each other.

Ask each function or area what it needed. Start with the parts and put each part on the site plan where it was best served.

An example is a breakfast area. Now most people eat breakfast in the early morning and may want the morning sun coming in the window. So that would locate the breakfast area on the east side of the plan. Continue this with all the areas of the house plan.

I call the function areas of the house the ‘Parts.’

Mr. Wright’s saying: “Part is to part as part is to, whole.”

This exercise is not a design it is the beginning of understanding the needs in relationship the conditional requirements of the project.

I learned to do this on the topographical site plan and place the parts of the areas on the site plan at the same scale. I made cutouts of each area like bedrooms, labeled each one and so could move these areas around on the site and in relationship to each other. The result was an organisational relationship. This is not a floor plan yet. What it does is point out the problems that need to be resolved. You learn very quickly that if the lot is small and the area needs are large that you will have a two-floor house.

Put each area in the best location and you will have some conflicts.

Mr. Wright’s saying: “The solution to the problem is contained within the conditions of the problem.”

Understanding the problem is the most important beginning. I learned not to start by sketching or making drawings.

So, what can I do? How can I make a design without drawing it?

Mr. Wright said that he did the design in his mind before any drawing. I said to myself “if Mr. Wright said it was the way he did it, I would try it.” After completely understanding the site and the requirements I did not focus on what the design could be. I did not look for an existing design to copy. I did not start sketching. I did something else, anything else.

As I was doing other things often a partial idea or even a way to solve one of the problems would come into my mind. These beginning ideas are not fully formed and need to be kept in the mind to develop. If you sketch them, you will freeze them and it will be more difficult to allow them to develop and change.

Mr. Wright said: “Let the idea stay in your mind until it more fully develops so you can visualize it and walk through it inside and outside.” When you can see the idea in your mind, then is the time to start to draw it.

I also start to think about a design by putting myself on the real site and seeing the features of the site all around me. I let the design develop around me. I do not look at the design from the outside but from the interior space in relationship to the site features.

Organic Space

I learned that Mr. Wright was not simply making floor plans, he was drawing plans that represented the space he had in his mind.

What is ‘Organic Space’?

It is not a room. It is not a box with holes for windows.

“Organic space shelters and defines but never limits or confines” is my way of putting the concept. The areas are in a relationship with the whole of the interior and the site features on the outside.

Jack Howe taught us not to trap space but to find a way to let it flow beyond.

Space is far more than area or volume.

Space engages and involves the mind of the person that is having the experience. This involvement invites the mind of the person experiencing the architecture to be in relationship to the architecture by completing the space in the imagination.

Space never confines. Space is always in relation to the beyond.

Space allows the mind to complete, in imagination that which goes beyond.

Organic Space shelters and defines but never limits or confines.

Some of the so-called organic shapes to my mind do not have this aspect of Space. They have curvilinear shapes that are called organic, but they are still boxes, because they confine and contain the same as a rectangular box. To be Organic, Architecture must have this quality of Organic Space. It must allow the mind of the person to freely play with the infinite just as it does in the out of doors in nature.

Buildings are made with a floor, walls, and a roof. How the architect does this makes all the difference. The usual way is a box room put together with a lot of other boxes. This is trapped space a kind of prison. To break the box, one must let the edges go beyond the walls and the roof. Just as the floor inside goes outside through a sliding glass door to the wood deck. The walls can also go from inside to beyond outside giving the feeling of openness and continuity. The walls become protective screens and masses of stone or brick with open glass areas between. The whole of the interior is in relationship with features of the site outside. The ways to do this are infinite and up to the designer’s talent. I always let the function guide my choices.

Mr. Wright’s saying: “Form and function are one.” This is architecture not sculpture art. What is important is the human being who will use the space."

|

| 'House for Betta,' 1998, by architect James Schildroth |

Wednesday, December 06, 2023

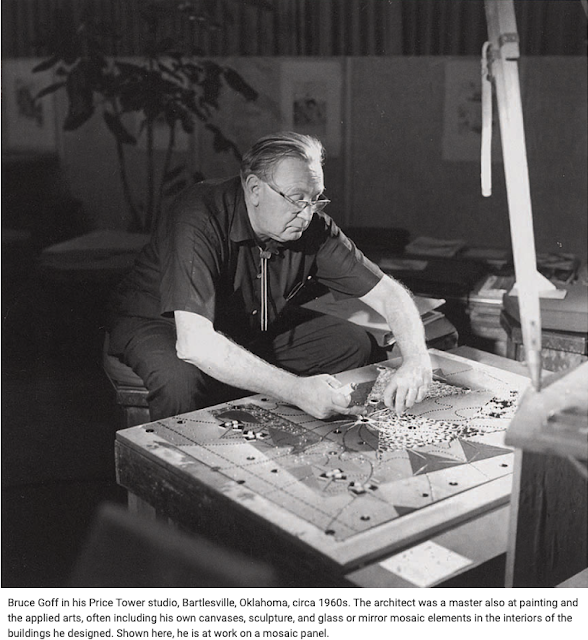

Bruce Goff: "As an architect..."

Architect Bruce Goff was a leader in what's been called "the other modern movement," i.e., the practice of organic architecture, pioneered by the likes of Goff, Frank Lloyd Wright, Aaron Green, and Walter Burley Griffin -- and after which Organon Architecture (in large part) bases its name.

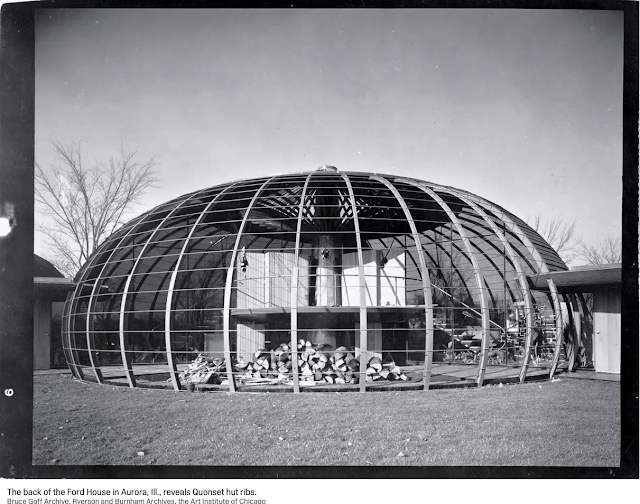

Bavinger House, Norman, Oklahoma, 1950-1955, no longer extant -

“the most amazing work of residential architecture I had ever encountered”

says Robert Morris (Photo by Anthony V. Thompson).

Goff wrote this piece below in 1978, four years before his death, for an exhibition of his work “Coda: As an Architect” essentially summarises his life as an architect and what a work of architecture is -- based on his expectation that a close relationship existed between all forms of artistic activity and life.

They seem like ideals by which to live and work ...

Coda: As an architect

I do not solicit clients they come to me as they would to any professional man for specific professional services.I do not work for clients…I work with them.

There has never been a building built before by anyone else or myself, that my client should have; we must work it out together. I forget what other architects and I have previously done so we can start as freshly as possible.

I must be sensitive to my client’s needs, wants and budget. I do not build upon a site…I build with it as part of its region, climate and environment.

I must be free from narrow-minded prejudices regarding materials, methods, colours, textures, forms, ornament, structure, and spatial determinates; all such aesthetic and utilitarian matters as felt and understood by the clients and myself must be freely disciplined by me, as an architect, into grammar from which will be composed the whole complete architectural concept.

There shall be no starting with a predetermined over-all shape or form in mind; no subdividing it off into rooms cluttered with furnishings…with the clients and their lives squeezed and compressed within. This is usual, and as usual in no more than the usual container for the use of humans!

Rather, the whole thing will start with accommodating people and their ways of life, and grow organically from within outward thus becoming its own shapes and forms.

If I give the client only what he asks for, he may be temporarily satisfied with it, for a while, but eventually he will just get used to it. As an architect I should give him what he wants… and more. If it is a work of architecture, the client will continue to grow aesthetically in such an environment…therefore there must be a continuing surprise and mystery beyond what he initially understood to hold his interest and to be a continuing, rewarding setting for his lifetime.

As an architect I know that technology and superb building techniques are necessarily a part of all of this, and we must be more aware of the ones we already have and of those new ones we need, but good building, in itself is not enough to be called good architecture, however, architecture is good building plus!

An architect’s works are personal and impersonal…timely and timeless; having a license to practice does not mean, in itself, one is an architect any more than having a driver’s license means one is a good driver. This is what separates the boys from the men.

The real architects are the young ones, regardless of age, with continuing enthusiasm, imagination, industry, inventiveness, curiosity, and dedication to architecture for all people as their reason for being.

Anything needing to be built, small or large, simple or complex should and can be architecture. We have many more people wanting this than we have architects able to supply their demands. We must never forget that architecture is for all of us.

As an architect, I know that our works often make some people mad and some glad.

The creative young are intrigued, inspired, and stimulated by them, as are those who use them. By such examples we continue to renew faith in the creative spirit and its potentials, thus, we are also teachers, but not academic.

I have never sought publication or publicity, preferring to let the work earn this for Itself if it is worthy, and so I too continue to “maintain my amateur standing” as a beginner, beginning again and again in the continuous present…

Bruce Goff, Architect, April 1978

Thursday, July 20, 2023

"The Need for Therapeutic Architecture in Today’s Society"

"With the rise in mental illness there is an increasingly strong need for therapeutic spaces," writes architect Abigail Freed. "Therapeutic architecture," she argues "lessens the need for the typical patient-doctor relationship. The space itself becomes the 'therapeutic apparatus'."

What a fascinating idea!

I've been told by some clients that our initial design interview is "a little like psycho-analysis." Architect Richard Neutra, a friend of Sigmund Freud, made that connection explicit. Explains Freed:

He required his clients to keep diaries and subjected them to a lengthy interview process. These tactics were Neutra’s way of gaining insight into their daily lives, their conscious and unconscious desire, their habits, their personal and interpersonal struggles and triumphs, as well as their deepest thoughts and feelings. Neutra believed that “architecture should operate like psychotherapy by assisting clients to satisfy unconscious psychical desires” and that the architect “operates on the basis of an emotional dynamic with a client developed through analysis of childhood experience.” From this process he felt fully equipped to create a physiologically curative design.”

Bethany Morse outlines his four-fold "biorealist" approach:

Abigail Freed outlines some of the "design tactics" Neutra used to fulfil the brief he gave himself, to better connect the "subject" to their environment and "imprint" upon them better mental habits.

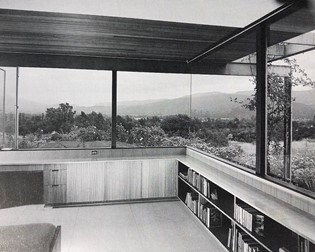

One of the most notable features “of Neutra’s work during the 1950’s was an intense concentration on dismantling conventional barriers between inside and out.” He achieved this effect through the implementation of various tactics such as transparent glass, “spider legs” and mitred glass corners.

In all of Neutra’s post war houses there is an emphasis on the glass exterior.

In the Rourke house (1949) “the outside world intrudes through large glass panels. These are not simply picture windows that frame views or glass walls that structure the house as in traditional… instead the glass window/wall is actually a door that moves and permits movement. The wide overhang of the roof creates a zone of shadow attenuating and extending the boundary of the interior. The overhangs that all but eliminate reflection further reinforce the indeterminate simultaneity of enclosure and exposure. The glass becomes not transparent but invisible to leave the house unbounded.”

Neutra used his Spider Legs (pictured above) “to collapse the normally primary architectural distinction between exteriority and interiority”. The spider leg is a single beam or fascia that “fascia stretches far beyond the edge of the roof at a major corner and turns down the reach the ground”. By displacing the corners of rooms and “in some cases the very structure of the house such normally stabilising architectural elements are indeterminately inside and outside at the same time.”

One of the most celebrated features of his architecture is the corner where one glass plane meets the other. At this corner the floor to ceiling glass meets at a mitred edge to produce a glazed environment of intense spatial ambiguity. Here there is a distinct oscillation between opacity and transparency, interiority and exteriority, solidity and fluidity and it generates perceptual confusion. Here the “glass and frame perform to both produce and suppress the edge of the house.” In the Moore House (1952) “the corner provided [Mrs. Moore] with a sense of the inter-relation of Nature without and living within that could do nothing less than eliminate the depression which we feel. She felt this interrelationship especially on a misty gloomy day, in other words when the house was at its most moody and when she turned to the window to get out, to enter its distant view over the far landscape and to join what she called the ‘mystery over the mountains’.” Neutra saw this corner as the precise moment where instabilities and uncertainties collect and where desires, both psychic and organic are projected.

“prospect,” meaning looking out above your surroundings from a commanding position … afforded by glass walls. In contrast, the kitchen and the bedroom/dressing area, with their walls of warm mahogany, create the counterweight to prospect in the quality called “refuge,” or shelter, or what Gaston Bachelard called the cave. Both prospect and refuge are necessary to us.

Bothe qualities, of course, would have been physically necessary when subject to potential attack by wild animals, or other humans! Now they are just as necessary psychically.

Neutra delivered a small space that feels expansive, not cramped, because it has an effect beyond its four walls. As he often said, his goal with small houses was to “stretch space” ...

One of his clients, Mrs. Logar, wrote to Neutra in 1956 (just four years after building the home in Granada Hills California) saying that she and her husband wished to sell their house. She states, “it looks messy all the time and there is no place to hide things away. We are entirely exposed to view from all sides. This is just about right for some executive and his wife. I think I prefer to live in an old hidden away place for a couple of years to clear my thoughts.”Mrs. Logar was exhibiting one of the common criticisms of Neutra’s homes: the feeling of vulnerability and extreme exposure that accompanied living in the glass house.

However this complaint is the home’s very success, not failure. Based on the Freudian understanding of empathy, which is defined as “an unconscious defense against internal impulses… to projection onto an inanimate object… into a defensive transfer of feelings onto another subject” it can be inferred that those who are experiencing these fears of exposure and vulnerability are actually experiencing their unconscious repressions becoming conscious. In the Freudian manner Neutra has brought to light what they have repressed since childhood- their fear of exposure and vulnerability- in order to overcome these fears and be cured of their neurosis.

Mrs. Rourke, contrary to Mrs. Logar’s opinion, “argued that Neutra had given them a new living experience [and she] could think of only one word to describe the way she felt about it: Liberation.”While Mrs. Logar failed to overcome her phobia, Mrs. Rourke’s statement suggests that she was able to embrace the vulnerability tied to exposure from all sides at all times and was rewarded with a improved quality of life. The “improperly bounded environments of these houses permitted psychoanalysis to be everywhere and nowhere at the same time. The houses’ naturalising materials, blurred structure, and camouflaged glass are both in the open and deliberately evade the gaze, enabling their therapeutic actions to be everywhere while out of view.”

This type of architecture is always a success if it at the very least helps those struggling feel as through they are helped. What is the harm if it relieves only the inner anxieties of some? Critics may claim it is “all in their head”, but that is the very basis of emotion -- we all exist in our own heads.Agree or not, perhaps the most important thing to take away is that our psychological facts and requirements are just as important to the design of our houses as our physiological needs, or the house's structural demands. They are all facts of existence that we must take into account in our designs.

Wednesday, June 21, 2023

Humble House for Hamilton

Here is why I call myself a "humble house designer": A humble wee house -- one of two, for the same extended family -- on a small well-surrounded site in Hamilton.

See of you can deduce the connection between this house, and Frank Lloyd Wright's explanation of what he means by the term organic architecture ....

Thursday, March 02, 2023

"The current building regulatory environment cannot genuinely support innovation without a major rethink."

"Concerns about the complexity of the [building] regulatory framework and its impact on innovation have been raised by BRANZ* in recent submissions to both the Commerce Commission and to MBIE....

"While the regulatory framework has been designed to allow flexibility to use new products [Ahem! - Ed], in practice, it has not been totally effective. We believe this is because the regulatory system is too complex and creates uncertainty around how to ensure a product will comply.

"This uncertainty then incentivises designers, builders and building consent authorities to favour tried and tested building products to ensure lower personal and organisation risk. In short, the complexity of the regulatory environment is driving behaviours and decisions across the building system that are risk averse, conservative and not conducive to innovation.

"[T]he current [building] regulatory environment cannot genuinely support innovation without a major rethink."~ outgoing BRANZ* CEO Chelydra Percy, in an unusually frank assessment of the regulatory impediments to innovation in the building industry, 'Holding Up a Mirror to the Industry'

* BRANZ, i.e., the Building Research Association of NZ is the government research body overseeing and appraising building materials and systems, funded by a compulsory levy on all Building Consents.a

Saturday, February 25, 2023

"By organic architecture, I mean..."

"By organic architecture, I mean an architecture that develops from within outward in harmony with the conditions of its being, as distinguished from one that is applied from without."~ Frank Lloyd Wright

Monday, December 12, 2022

Architecture by Artificial Intelligence. Too soon?

Are architects no longer needed to come up with ideas?

Can we get the new Artificial Intelligence engines to dream up ideas for our projects, and others to then draw them up to get consented, and built?

Just for fun, I had a look at the DALL-E engine, that spits out images created on the spot, however crazy your request.

I tried a few phrases based on current projects.

These four below were generated by the search term 'Auckland apartments by Frank Lloyd Wright' ...