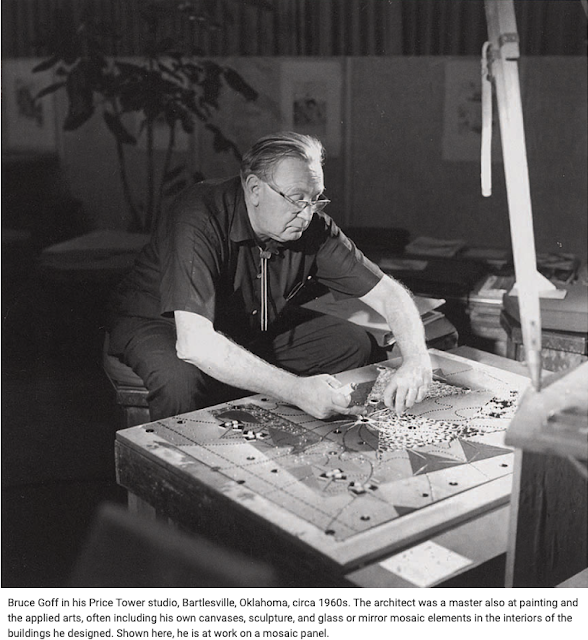

Architect Bruce Goff was a leader in what's been called "the other modern movement," i.e., the practice of organic architecture, pioneered by the likes of Goff, Frank Lloyd Wright, Aaron Green, and Walter Burley Griffin -- and after which Organon Architecture (in large part) bases its name.

Bavinger House, Norman, Oklahoma, 1950-1955, no longer extant -

“the most amazing work of residential architecture I had ever encountered”

says Robert Morris (Photo by Anthony V. Thompson).

Goff wrote this piece below in 1978, four years before his death, for an exhibition of his work “Coda: As an Architect” essentially summarises his life as an architect and what a work of architecture is -- based on his expectation that a close relationship existed between all forms of artistic activity and life.

They seem like ideals by which to live and work ...

Coda: As an architect

I do not solicit clients they come to me as they would to any professional man for specific professional services.I do not work for clients…I work with them.

There has never been a building built before by anyone else or myself, that my client should have; we must work it out together. I forget what other architects and I have previously done so we can start as freshly as possible.

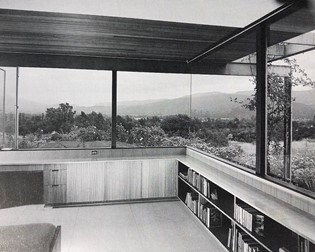

I must be sensitive to my client’s needs, wants and budget. I do not build upon a site…I build with it as part of its region, climate and environment.

I must be free from narrow-minded prejudices regarding materials, methods, colours, textures, forms, ornament, structure, and spatial determinates; all such aesthetic and utilitarian matters as felt and understood by the clients and myself must be freely disciplined by me, as an architect, into grammar from which will be composed the whole complete architectural concept.

There shall be no starting with a predetermined over-all shape or form in mind; no subdividing it off into rooms cluttered with furnishings…with the clients and their lives squeezed and compressed within. This is usual, and as usual in no more than the usual container for the use of humans!

Rather, the whole thing will start with accommodating people and their ways of life, and grow organically from within outward thus becoming its own shapes and forms.

If I give the client only what he asks for, he may be temporarily satisfied with it, for a while, but eventually he will just get used to it. As an architect I should give him what he wants… and more. If it is a work of architecture, the client will continue to grow aesthetically in such an environment…therefore there must be a continuing surprise and mystery beyond what he initially understood to hold his interest and to be a continuing, rewarding setting for his lifetime.

As an architect I know that technology and superb building techniques are necessarily a part of all of this, and we must be more aware of the ones we already have and of those new ones we need, but good building, in itself is not enough to be called good architecture, however, architecture is good building plus!

An architect’s works are personal and impersonal…timely and timeless; having a license to practice does not mean, in itself, one is an architect any more than having a driver’s license means one is a good driver. This is what separates the boys from the men.

The real architects are the young ones, regardless of age, with continuing enthusiasm, imagination, industry, inventiveness, curiosity, and dedication to architecture for all people as their reason for being.

Anything needing to be built, small or large, simple or complex should and can be architecture. We have many more people wanting this than we have architects able to supply their demands. We must never forget that architecture is for all of us.

As an architect, I know that our works often make some people mad and some glad.

The creative young are intrigued, inspired, and stimulated by them, as are those who use them. By such examples we continue to renew faith in the creative spirit and its potentials, thus, we are also teachers, but not academic.

I have never sought publication or publicity, preferring to let the work earn this for Itself if it is worthy, and so I too continue to “maintain my amateur standing” as a beginner, beginning again and again in the continuous present…

Bruce Goff, Architect, April 1978