“Whatever space and time mean, place and occasion mean more. For space in the

image of man is place, and time in the image of man is occasion. ... We are not

building buildings, we are building ritual, building occasion, building life itself.”

~ Claude Megson (after Aldo Van Eyck)

Over the last two days we talked about man and how to begin making a home for him on this earth: It’s not just about marking a spot; it’s about making places: human places, for human occasions.

But isn’t it the case that much of our built environment, and hence much of what architects do, is normally beyond our immediate awareness? Most people just don’t notice too much about the buildings they’re in, do they (at least not consciously) – they quickly become ‘second nature’ to us, unless of course something goes wrong!

We might ‘feel’ a space or a building as being good or bad or uplifting or stultifying or bland or glorious … but we don’t always consciously know why. So let’s start looking at what architecture is trying to say to you, and how you can begin to ‘listen.’ And let’s literally start in the home . . .

Part 3: The essence of the home

“A house is not an object but a universe we construct

for ourselves – not a garage where we park ourselves.”

~ Claude Megson

SINCE WE TEND TO take for granted the architectural experiences we are offered, so Jay Farbstein and Min Kantrowitz in their book People in Places suggest a starting point for learning to understand what architecture can say to you if you let it (assuming of course that the architecture has something to say!):

Architecture [they say] begins with the five senses, plus other (sub-senses) like those to do with temperature, humidity, air movement across the skin, and especially the kinaesthetic or haptic; the senses must come first!

Next, These sensations must be integrated into patterns i) of day-to day life – entering the house, engaging in conversation, cooking, eating, watching television, bathing, lying in bed – and ii)of integration with the wider world with the perceiver at the centre – detailed and complex recognition of siting, eye lines into the distant ( and close) landscape.

Of harbour, valley and hilltop (each with their own resonance for us) and even the gradual exclusion of the public realm (“this is our space”) down to individual realms (“this is my space”).

Architecture recognises and builds in all these patterns or rituals – try and identify them in the place you’re in now, and think too about that special place from childhood and see how its patterns go together, and if they played some part in making it special for you.

The point here is that all architecture begins with you – it doesn’t begin with some gods-eye view from above, or from some arid analysis of string-courses and pendentives. It starts from the point of view of the observer, of the person experiencing the whole ensemble---it starts there, and it radiates out1.

From this starting point then, architecture needs to integrate the material sensed (nothing should be accidental in art), and integrate it conceptually into a pattern that gives to the person experiencing it a meaning to life on this earth. It should be life-enhancing, on a distinctively human scale, because, as we’ve said, architecture is about making a home for man - literally MAKING a home for man – and at the same time EXPRESSING the facts about our world and our place in it, and then underscoring whatever emotional evaluation follows from that.

* * *

Sometimes the house grows and spreads so that, in order to live in it, greater elasticity of daydreaming, a

daydream that is less clearly outlined, are needed. "My house," writes Georges Spyridaki, "is diaphanous,

but it is not of glass. It is more the nature of vapour. Its walls contract and expand as I desire. At times,

I draw them close about me like protective armour .. But at others, I let the walls of my house blossom

out in their own space, which is infinitely extensible.” Spyridaki's house breathes. First it is a coat of armor,

then it extends ad infinitum, which amounts to saying that we live in it in alternate security and adventure.

It is both cell and world. Here geometry is transcended.

~ Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

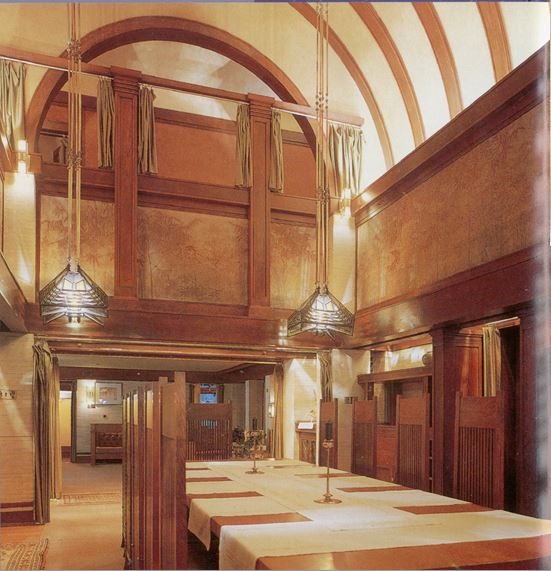

AS WE’VE SEEN in Part Two of our story, the essential meaning -- the very essence of the dining occasion-- is celebration. Giving to a home this essential human meaning of celebration is what we’re doing when we build a space for dining (or, if we’re not very good, we build something that might give almost the opposite impression).

Thus, the essential meaning given to the dining space of a home should be celebration.

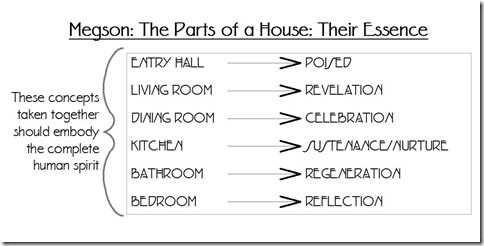

In the same way, architect Claude Megson suggested that every space in a home has its own essential human meaning that must be given its essential place and expressed appropriately in the architecture (and in the following outline I use Megson’s schema). When we build a house, in the words of Megson “we build a whole universe for ourselves to inhabit” – that place must reflect our whole universe of needs and emotions. The universe of our own soul. So let’s take a tour round our ‘soul,’ and the essence of all that it contains.

If our Dining area isn’t just a place in which to gnaw on a raw bone, then the Bathroom isn’t just a place to hose ourselves down. It is, or should be, a place wherein we experience our physical selves (visuall via our mirrors) and receive our full physical sensation of being; a place in which to cleanse and refresh ourselves both physically and spiritually (it’s no accident that religionists adopted bathing as a symbol of baptism.) It should express, if we can manage it, a feeling of cleansing and rejuvenation -- almost of rebirth.2 The term used by Megson was “Regeneration.” That, oddly enough, is the feeling a good bathroom should give.

Just to clarify here: A good bathroom, or indeed any space designed and built properly, should both support the function intended for that space, and at the same time express the meaning -- the essence – of the space. Both feeling and function are equally important – indeed, the feeling is an integral part of the function that needs to be built into the form I f form and function are realy going to be made one. (And as Frank Lloyd Wright said on a somewhat related subject, if done properly “form and feeling become one.”)

So Dining = Celebration; Bathroom = Regeneration. What else needs to be expressed in Megson’s schema?

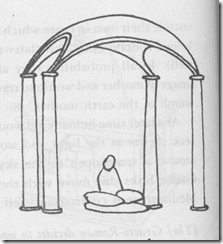

Our Living Room is the place where life reveals itself; wherein a stage is set for our lives, for all our entrances and exits; a place of both continuity and permanence; both adventure and security; a place for books, for relaxation, for discourse, for the good news and the disappointments of our lives; for the gatherings and the adventures and occasional withdrawing from the world we all do and need to do .. the place wherein the nature of our selves is worked out and revealed, with all the other spaces in the house acting as support.

And like a stage (and like our own private souls) the Living Room both exposes and hides us: as Gaston Bachelard explains the house should sometimes be around us like an armour, like a cloak, and at others it should hardly be there at all.

Most of all, a living room should express the adventure of life. All these things described in the living space reveal the nature of a full life, so the living room as a who;e shows us the whole cosmos of life. If dining is a mark in time, then our living rooms should reveal a sense of the infinite. So a Living Room worth its name must both support the function of lounging, and at the same time it should, Megson argues, express the concept of Revelation. That concept, he argues, best describes the human need fulfilled in our best Living Rooms. In this place, more than in any other part of the house, this concept should be most evident.

The Entrance: Here is our hinge, our place of welcome and farewell, the place in which we are midway between coming and going, where we are poised “cat-like” between entrance and exit, between rejection and welcome … a dynamic equilibrium representing the occasion of greeting; the concept best expressed here is Poise.

The Bedroom is our ultimate place of withdrawal; our place for solace and sexual excitement, for peace and repose, and for reflecting, planning and dreaming. Bedroom = Reflection.

The Kitchen is the place in which life is sustained and nurtured; in which the first lessons are learned of chemistry and physics; of safety and danger. The essence of the Kitchen is Sustenance, or Nurture.

All these functions and feelings and meanings take place under one roof, in one house. In the same sense that all artwork is making a statement about the world in which we live – whether the artist likes it or not -- every piece of art is a microcosm of what the artist considers to be fundamentally important within this universe – so too the house should contain a whole universe in microcosm.

In Megson’s words, the house is not just a garage where we park ourselves; nor is it merely an object: it is instead a whole universe we construct for ourselves -- “it should embody the complete human spirit.”

This is how we go about our task, of making a home for for man . . .

NOTES

1. A point to anyone who can see the similarity to Austrian economics, or to Montessori education.

2. We cleanse ourselves of ‘the outside’ while symbolically cleaning ourselves within; we emerge physically revitalised and metaphorically reborn. (It is no accident that bathing is the essential religious symbol of baptism.)

Water represents purity; as does its complement, light; which together produce an essential sparkling, uplifting effect.

[Cross-posted to the Claude Megson Blog]