If we’re going to make “a home for man,” as we talked about in Part One, we need to know why man needs a home. And to answer that there’s a more fundamental question we have to address first . . .

* * * *

Part 2: What is a Man?

Hamlet: What is a man?

If the chief good and market of his time

Be but to sleep and feed? A beast, no more.

~ William Shakespeare

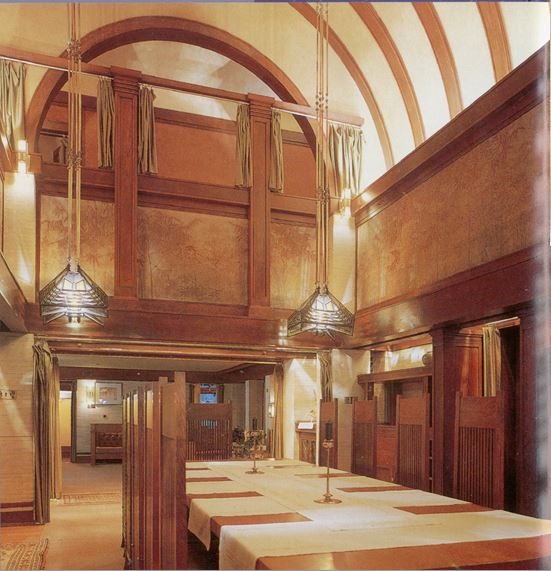

LET’S BEGIN TO ANSWER our two questions – what is man, and what it means to make a home for him -- by looking at two very special spaces which will help us get a grip on what sort of people we human beings are, and what ‘home’ means to man: two dining rooms (pictured below) created by Frank Lloyd Wright, one in 1902 for Susan Lawrence Dana, and the other in 1941 for an un-built project. Each one creates a space for people to celebrate the event of dining together, because for humans the act of dining together is something to celebrate. Not just time for a feed, but a stop, a reward for succeeding at the job of existence.

Wild animals hunt down their food and eat it raw. A lion rips the innards out of a lesser beast and eats it while the blood is still warm, and the heart still beating. A hyena finds the windfall and tears the remaining flesh from the bones, and vultures fortunate enough to discover the remains pick over what’s left.

Not us. That’s the way of the beast. We’re animals, true, but we’re rational animals. Our enormous brains have enabled us to succeed at life, to plan ahead, to flourish and to celebrate our successes. If the chief good and market of our time be but to sleep and feed, then we truly are no more than a beast. But we don’t just do this. We don’t just gnaw on a raw bone then fall asleep in a darkened cave: we sleep in comfort and we eat gloriously prepared food in the most elegant surroundings we can manage with the people we like and admire, and we celebrate we can do that by building into our homes this important ritual –this occasion.

In this sense, a dining space is not just a place to eat and be fed; it is the place in which we mark the occasion of dining – a place in which we share in goodwill the goods of the world together; where we mark the occasion of coming together, of our celebratory. Understood this way, as architect Claude Megson explained, the one-word essence of our dining space is: Celebration.

In a very concrete way then, architecture is simply built-in ritual, making a special place to host each of our special occasions.

From man’s earliest days, we’ve marked the things of importance to us with our rituals. The ritual of saying Grace at dinners has a good secular reason, a pause for thanksgiving, a moment in which to reflect on our success in providing for ourselves.

Man raises himself above bestiality partly by a simple elegance that speaks to who we are and what we need, and partly by marking these regular rituals as something life-sustaining. As architect Claude Megson used to say (echoing Aldo Van Eyck),

whatever space and time mean, place and occasion mean more. For space in the image of man is place, and time in the image of man is occasion. ... We are not building buildings, we are building ritual, building occasion, building life itself.

If you’re a Frank Lloyd Wright, then you do it in a particularly life-enhancing manner.

Frank Lloyd Wright: Dining space, Susan Lawrence Dana House, Chicago - 1902

Note for example those two very different dining areas by Wright, above and below. Study them, and try and imagine yourself there—how it might feel to be there. Note for instance the lighting fixtures, the high-back chairs and the moulding lines, all of which help to contain the seating group and also to bring the focus of the diners’ attention down to the group, making it a smaller, cosier space but still part of a much larger space in which the diners are framed by the seating, and their faces lit up by the lighting fixtures to become the centre of interest that they should be in such a gathering.

Frank Lloyd Wright: ‘Sijistan’ Project, 1941

The vaulted ceilings contain, gathering without overpowering – like a tent canopy above – giving a very human scale to what is quite a large ensemble. Warm colours and special detailing massage the space to fit the occasion – offering the sense of a group that is gathering together to celebrate their own efficacy, the bounty they have produced, and their joy in each other’s company. In short: a celebration of thanksgiving – every day.

“ARCHITECTURE,” AS FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT SAID, “makes human life more natural, and nature more humane.” And THAT is the starting point of understanding the meaning of architecture: that it’s about life – human life – in ALL its forms – literally all of its forms – and the job of architecture is to keep us connected to what’s important in our lives; celebrating our important occasions; making the most of the material the earth provides in all its forms, and at the same time mediating, excluding and shutting out that which isn’t wanted.

Hamlet’s question above affirms for himself that “the unexamined life is not worth living” He’s right. ‘Building in’ such simple rituals as our celebration of dining gives us the opportunity to daily examine and celebrate our lives as we go through those daily rituals that give and keep on giving meaning to our lives. The result is a heightened sense of existence connecting us to our most fundamental values. “We build our homes,” said Winston Churchill, “and then our homes build us.” And so they do.

What good architecture does is to deal with the totality of a human existence, to provide at one level the support structure to make human life possible, and at another much richer level to express back to us what it means to be human by giving a sense of place to all our occasions, by building in all our important rituals, by connecting us to what is meaningful in our lives: To sunrises and sunsets; to the sharing of food together; to relaxing with friends; to having time and space for contemplation and for conversation, and for rest, and for sex -- and for rest and contemplation (and conversation) after (and during) sex.

That’s about as important as a job gets, right?

* * * *

BUT ISN’T IT THE CASE that much of our built environment, and hence much of what architects do, is normally beyond our immediate awareness? Most people just don’t notice too much about the buildings they’re in, do they (at least not consciously) – they become ‘second nature’ to us -- unless of course something goes wrong!

We might ‘feel’ a space or a building as being good or bad or uplifting or stultifying or bland or glorious … but we don’t always consciously know why. So tomorrow, we start looking at what architecture is trying to say to you in your home, and how you can ‘listen.’

RELATED POSTS:

- “The purpose of architecture is to make a home for man.” ~ Aldo Van Eyck

Architecture: ‘Making a home for man’–Part 1 - ““Architect Dominic Glamuzina says [the Megson house] invokes the feeling that one should have a cocktail in one’s hand at all times while wandering through it.”

Quote of the day: But isn’t this how every house should feel? - “The home is a shelter, not a fortress.” That was the ethos behind the post-war Usonian community built amidst a heavily wooded site in Pleasantville, upstate New York, guided by the masterplan of architect Frank Lloyd Wright.”

Lessons about landscape: doing subdivision Wright - “If we want to “break the box” instead of make a box when we build our houses, then we need to shake a few tricks up our sleeve.

Architectural Mini-Tutorial: Organising our visual field - …“the other modernism.”

Organic Architecture

No comments:

Post a Comment