“The purpose of architecture is

to make a home for man.”

~ Aldo Van Eyck

The purpose of architecture is not just to look nice in magazines. In five words or less, the primary purpose of good architecture is: giving meaning to our lives. To quote the late, great New Zealand architect Claude Megson, "If it doesn't have meaning, then you're just wanking."

In this three-part post, I argue that architecture ‘marks our spot,’ engages our spirits, and tells us daily who we are.

Read on to begin . . .

*** WHEN MAN FINALLY CONQUERED mountain, when Hillary and Tenzing reached the top of Everest for the first time, the story goes that Tenzing fell to his knees and gave thanks to the spirits that had helped their journey; he prayed to each of the four winds who had remained in abeyance; and he carefully placed in the ground at each compass point a small stake on which prayer ribbons were attached. While he was doing this, Hillary stuck a flag in the ground, unzipped his fly and took a piss.

We each mark our territory in very different ways. But we do each mark our territory.

We make buildings to keep the rain off, and in doing so we raise a crown over our head and mark out from the world our own space below.

We mark out for ourselves a place in the world by building a campfire that we keep burning and around which we make comfortable for ourselves, or by raising high our own totem that seems to say “here I am!”

We recognise the important rituals we’ve built into our own lives by making these rituals concrete, literally making them concrete, and by doing so we are saying, “This is important.”

We erect buildings to perform some useful function, and in the act of erecting them they unavoidably perform another crucial useful or symbolic function for us: They embody our values. They tell us we exist. They show us who we are.

Buildings are a concrete expression of values – the values of the people who commissioned, designed, erected and occupy them.

Like every art, architecture is a shortcut to our philosophy. In building architecture we erect an armature that will support ourselves and our important values, and offer us as a place from which to look out upon the world around us. Amongst the myriad of ways this could be done, we each choose the one that does it for us. Live every artformm architecture is a shortcut to our philosophy – which is why our choices are so often so personal to us. The way architecture does that is as an extension of ourselves.

Architecture, as architect Aldo van Eyck says, is about ‘making a home for man.’The space we build is space for human life, for us to inhabit, and from which we can emerge to 'do battle.' It is a place that expresses what a home for man looks like, smells like and sprawls like; it is here that we begin to find the meaning in architecture: the meaning resides in how it makes its home for man.

In the act of making and placing our buildings in the world, we make decisions about what’s important in the world. What values need to be 'built in' and made concrete.

- What should we include from the immediate environment around us?

- What of oit should we keep out?

Early morning sun is good; later-afternoon sun often isn’t. Gentle breezes are good inside the house; heavy rain is not. Views of the lake and the trees and the beautiful hills about us are wonderful – views of the local slaughterhouse are not.

Some of these things are highly contextual. Early morning sun is great in Reykjavik, but not always in Dubai in mid-summer. Later-afternoon sun is bad in most parts of the world, but in Murmansk, inside the Arctic Circle, “late afternoon” extends for several months, and is always a welcome guest. Gentle breezes in Hawaii are welcome; in Siberia they might be called a draught. A view of the local slaughterhouse from your lounge window might be highly prized if you’re … okay, I’m stretching on this last one.

The fact remains nonetheless that the choices we make about how we build our shelter, mark our place and decide what functions our building serves for us define something both about us, and about the place we make -- and about the context in which we make it.

HERE’S A VERY BASIC fact from which we start:

WE NEED TO BUILD.

Why so? Animals in general adapt themselves to nature, and they’re mostly already adapted to do that. But humans can’t. We adapt nature to ourselves. We must. We either adapt nature to ourselves, or we die. Unlike animals with their claws and armour, their feathers and strong hides, with all their multiple defences against the world, we human beings have but one: our reasoning brain. On its own this offers no physical defence against predation, and no guarantee of survival: we must learn to use our brain to plan, to invent, to create; to understand the nature of the world around us and to make sense of it and to adapt it to ourselves; to make of it a place in which we are protected, and (as we become more accomplished and learn more about our psychological as well as our physical needs) a place in which we can feel ourselves at home.

We need buildings to shelter us, and not just in the physical sense of shelter. We need a place that is a home: our place, wherein we see ourselves and our own values reflected back, including the value of the home itself and all of us it contains. (When we build a house, in the words of architect Claude Megson, we don’t just build a roof over our heads, “we build a whole universe for ourselves to inhabit” – that place must reflect our whole universe of needs and emotions; the universe of our own soul. In Part 3, we’ll take a tour around our ‘soul’ as reflected in our houses.)

Good architecture then is not just functional on the bare physical plane. We've been out of the caves long enough to do much better than that. “A house is a machine for living,” declared Le Corbusier on behalf of today's cave dwellers. “But only if the heart is a suction pump,’ responded Frank Lloyd Wright.

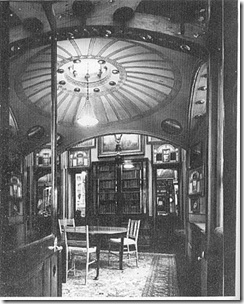

Architecture is not just shelter; it is not just ‘marking a spot’: its function is also to delight. Our crown might become a dome . . .

Bread and water nourish our stomachs; we need also to nourish our souls. Thirteenth-century Persian poet Muslih-uddin Saadi Shirazi offered this wisdom:

If of thy mortal goods thou art bereft

And from thy slender store

Two loaves alone to thee are left

Sell one, and with the dole

Buy hyacinths to feed the soul.

But buy them only if your heart is not a suction pump.

What good architecture does then is to deal with the totality of a human existence, to provide at one level the support structure to make human life possible, and at another much richer level to express back to us what it means to be human by giving a sense of place to all our occasions, by building in all our important rituals, by connecting us to what is meaningful in our lives: To sunrises and sunsets; to the sharing of food together; to relaxing with friends; to having time and space for contemplation and for conversation, and for rest, and for sex -- and for rest and contemplation (and conversation) after (and during) sex.

That’s about as important as a job gets, right?

Writing about Ferraris, PJ O’Rourke expressed it this way: “Only God can make a tree, but only man can drive by one at 250mph.” THAT is the feeling good architecture should communicate! We take the material that nature provides, and the needs that we have, and those moments where we say to ourselves, “Ah, this is what being alive is all about!” and we give those needs wings -- and we build in and celebrate those moments, and by doing so we express our lives, and we help bring meaning to them.

What could be more important?

In Part 2, we’ll answer the question: if architecture is about ‘making a home for man,’ then what exactly is man?

And in Part 3 we’ll discover what it is about man that needs a home—and we’ll take a tour of the ‘places’ he needs a home for.

No comments:

Post a Comment